Fall 2020

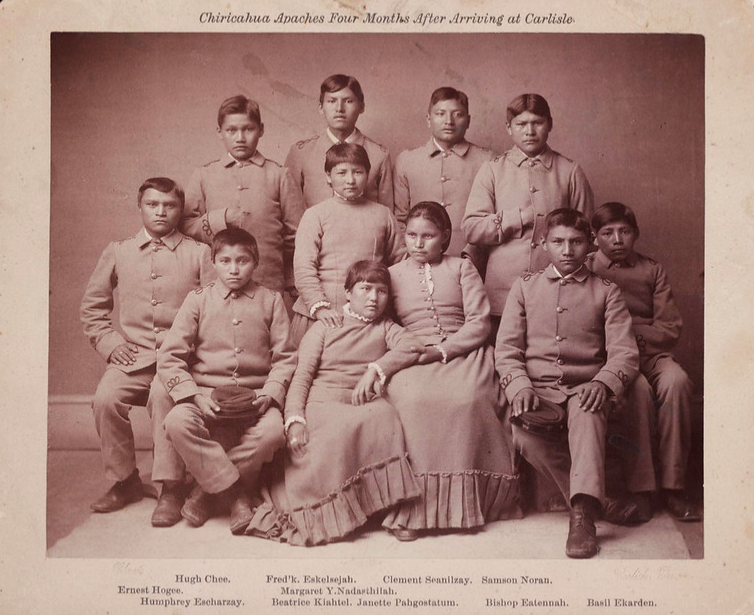

“Chiricahua Apaches Four Months After Arriving at Carlisle,” Richard Henry Pratt Papers, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Public domain.

The Indian boarding school system was a national system designed to erase Native culture and create a generational gap in Native communities. In 1879 Henry Richard Pratt, an American General, founded the first off-reservation Indian boarding school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. By 1900, Congress had appropriated almost $3 million to fund 106 boarding schools. The Indian boarding school system was the strategy that the United States government turned to after confining Native Americans to reservations had failed to strip them of their culture. The US government wanted to assimilate Native Americans into white society so that they could be used to benefit the nation. In order to do this they believed that they had to first dissolve the Native Nations’ ways of life so that they would be forced to adopt the new, imperial and capitalistic culture of the US. The Dawes Allotment Act of 1887 and the Indian boarding school system were the two prongs of the newest attack that the US government launched against Native peoples (Calloway 2019). The purpose of this essay is to illuminate methods of resistance and resilience, and to show that there were other long-lasting and widespread ways in which the US government assaulted Native peoples other than on the battlefield and in the courtrooms. The classroom was a different kind of warzone, but a warzone nonetheless.

The challenges that students at these schools had to overcome were both physical and mental. Students had to cope with extreme changes in diet and lifestyle, periodic beatings, sexual abuse, as well as emotional trauma. The mental strain of adjusting to this new existence was exacerbated by the fact that children were separated from their parents, given new names, haircuts and clothes, then told they could not speak their own language, which was oftentimes the only one they knew (Calloway 2019). Nowa Comig and Little Moon, two Indigenous men who attended Indian boarding schools reflected on the experience, describing their treatment there as “torture” and “brainwashing.” Nowa Comig laments the fact that his time at school permanently ruined his relationship with his mother (Nelson 2020). The connections that the US government sought to sever were religious, cultural, social, and familial. Even surviving this time away from home was a feat, but students were also able to implement various strategies to resist.

It is important to understand that not all students had the same experience at the boarding schools. (There were many students across the years and not all of their varying experiences can be represented, even generally, in this essay. However, it is safe to say that these institutions were violent and abusive spaces far more often than they were not.) Some children used their native tongue in secret to create a sense of community with their peers and strengthen their identities (Nelson 2020). Others pretended not to know their native language when they returned home to their family because they had been beaten countless times for speaking it and taught that it was something to be ashamed of (Standing Bear 1933). Many Native Americans engaged in small acts of rebellion while at the schools, but resilience also took form after tenure at the schools. Some alumni were able to use the writing and arithmetic skills that they gained to help support themselves and their communities. Some were also able to utilize these new abilities to fight for the sovereignty of their people. One Hidatsa man, Chief Wolf, used his arithmetic skills to open a shop back on his reservation, then used his writing ability to bombard the local branch of the Office of Indian Affairs with letters, berating them for their mistreatment of the communities they were meant to support (Calloway 2019). Some students, like Ohiyesa, a Santee Dakota physician and writer, went a step further. Ohiyesa ended up going to college then returning to his home reservation to use his newfound knowledge to heal and advocate for his community (Beane 2018). Others, like Luther Standing Bear, were able to connect with some of the teachers, but actively resented the school they attended (Standing Bear 1933). Yet others never made it home. Many students died during their term at the boarding schools either from diseases like tuberculosis or from suicide (Calloway 2019). Overall, there was a wide range of experiences in these boarding schools, but they were ultimately a tool for the US government to carry out their plan of assimilation and transformation of Native Americans into a more “civilized” group of people. Native peoples’ resistance to the horrible tactics of the boarding schools, and their ability to come out the other end with dignity, pride, and a will to evoke positive change is inspiring.

References

Beane, Syd, dir. 2018. Ohiyesa: The Soul of an Indian. Vision Maker Media. Kanopy.

Calloway, Colin G., ed. 2019. First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History. 6th ed. Boston: Bedford / St. Martin’s.

Nelson, Stanley, dir. 2009. Wounded Knee. PBS. Kanopy.

Standing Bear, Luther. 1933. “What a School Could Have Been Established.” In First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History, edited by Colin G. Calloway, 6th ed., 416–20. Boston: Bedford / St. Martin’s.