Fall 2021

During the Progressive Era, Native people repurposed settler colonial systems in order to protest their treatment at the hands of the U.S. government and rewrite harmful narratives surrounding their existence. In particular, this period from the 1890s to the 1920s saw many Native people use the colonial educations they received—or were outright forced into—to push back against those very same colonial systems and institutions. This was in itself a powerful form of resistance in a time when

“schools for Indians […] were more than government programs; they were expressions of a uniform conviction that Native American culture had no place in the modern world”

(Hoxie 2001, 9)

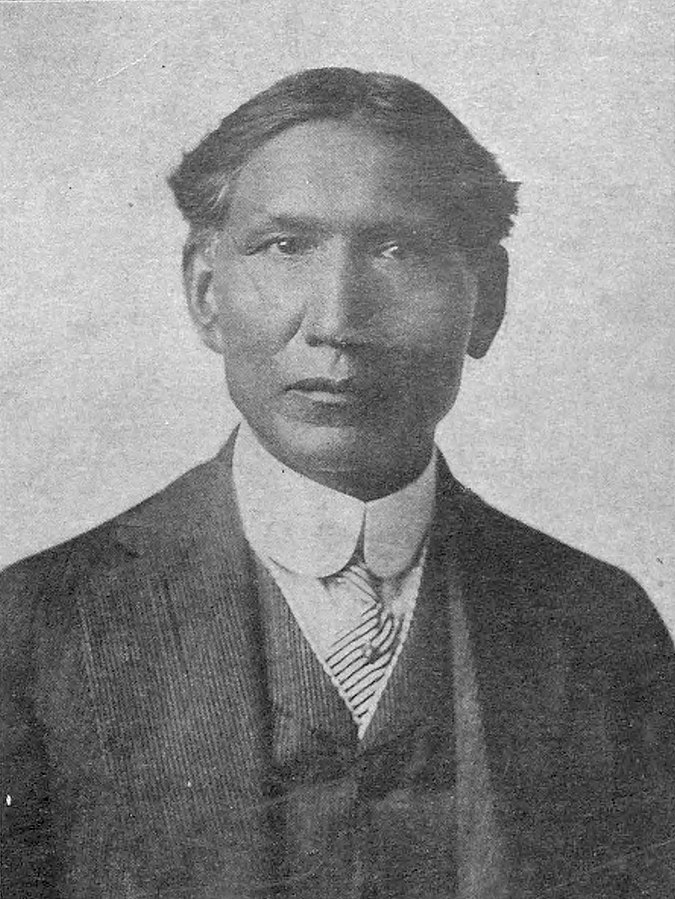

Boarding schools were the most infamous colonial education system, created by the United States towards the end of the 19th century in an attempt to erase Native cultures, languages, and identities (see: Resistance and Indian Boarding Schools). Ohiyesa (also known as Charles Eastman), an influential Santee Dakota advocate, doctor, author, and lecturer during the Progressive Era, attended one such boarding school—the Santee Normal Training School in Nebraska—and later studied and graduated from Dartmouth College in 1887 (Calloway 2019, 392-393). He became the second Native doctor certified in European-style medicine in the United States, eventually working for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) as a physician and quickly finding himself repurposing his colonial education to treat the wounded at the Massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890 (Beane 2018). He later became an author and went on the lecture circuit, using his public prominence and platform in tandem with his colonial education to affirm the value of Native experiences to non-Native audiences.

He consistently pushed back against the narratives that Native people were ‘uncivilized’ or were disappearing entirely by using “his education to put himself in an uncomfortable position of working for a system that was historically put in place to oppress” Native people.

(Beane 2018, 45:31)

In all, Ohiyesa found many ways to repurpose his colonial education to care for his community and push against harmful narratives about Native people.

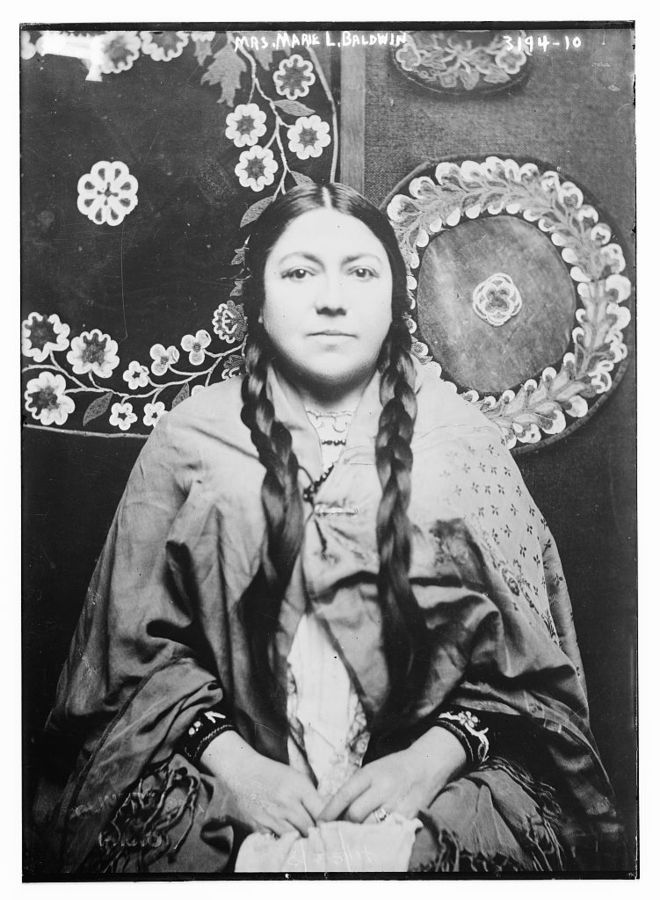

Not all activists agreed with Ohiyesa’s actions and views, however. Indeed, while he “had been raised in the traditional ways and remained strongly attached to Sioux values,” he also “worked to bring about assimilation of Indians into mainstream society” and worked for the BIA (Calloway 2019, 393). This marks a broader theme regarding Native resistance during the Progressive Era (and beyond): Native figures and nations each held unique views on activism, oftentimes disagreeing on the ends of their work and the means with which to achieve them. Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin, an influential Ojibwa/French figure, also found herself being criticized for her assimilationist views in her early career and her employment in federal office. Nevertheless, her work from the late 1800s through the 1920s, like Ohiyesa, provides another example of repurposing colonial education as a form of protest.

Educated in Minneapolis public schools and the Catholic St. Joseph’s Academy in St. Paul and the first Native person to graduate from the Washington College of Law (1914), Baldwin “served as an employee in the Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) for twenty-eight years [starting in 1904], yet she [also] became an active member of the Society of American Indians (SAI), an organization that often criticized the OIA” (Cahill 2013, 65-69). She repurposed her education from her father, an attorney for whom she worked as a clerk, along with her formal law school education to do highly influential work in federal office. From her position in the OIA, Baldwin promoted a positive image of Native people in order to seek solutions to problems that many Native people faced, often via federal policy, and “became a friendly Indigenous face in the Indian Office for many Native people” (Cahill 2013, 71). From her dual roles in the SAI and OIA, she also played a key role in monitoring legislation that impacted Native people, providing invaluable insights to the SAI while advocating for Native rights within the OIA. In these ways, Baldwin used her education in colonial schools in tandem with her father’s teaching to advocate for, rewrite negative narratives about, and pursue legislation that would directly benefit Native people. On the flip side, however, though she “tried to use her position to advocate for Native people in the public sphere,” more radical Native thinkers “critiqued the choice of Native employees like Baldwin to work for the Indian Office” (Cahill 2013, 83).

One such radical thinker was Carlos Montezuma (Yavapai Apache), who used his position in the SAI to call out Native “federal employees as disloyal to their race” (Cahill 2013, 80), because “The system that has kept alive the Indian Bureau has been instrumental in dominating over our race for fifty years” (Montezuma 1914). Instead of working from within an oppressive system to make change, as Baldwin did, Montezuma joined Piute activist Sarah Winnemucca in attempting to “shape, temper, or expose U.S. policies” from public positions (Calloway 2019, 375).

Both used their education and prowess in writing to publish scathing articles and books to “‘talk back’ to colonizers, oppressors, and bureaucrats who stifled Indian life,” describing—often for largely white audiences—the brutal hypocrisy of the U.S. Government and its ‘civilization’ policies (Calloway 2019, 9).

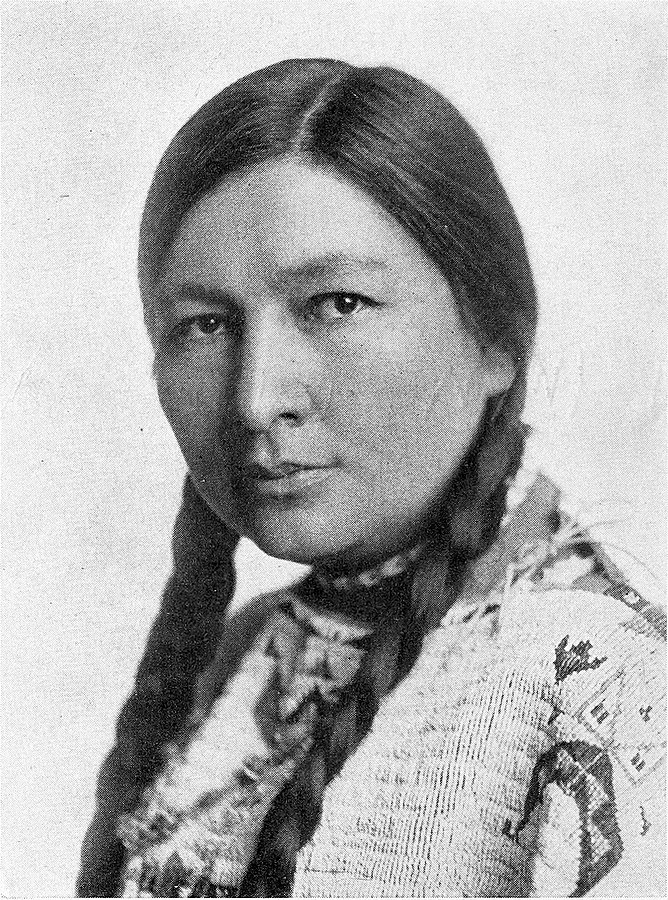

For example, Winnemucca’s book “Life Among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims,” published in 1883, was a “detailed book about everything that had been done to her people […] as a result of colonial power and control” that, among other injustices, described in explicit terms the sexual assault and violence that Native women and children experienced at the hands of settlers” (Deer 2019, 21:37). Gertrude Bonnin (Zitkala-Ša, Yankton Sioux), another influential Native figure and member of both the OIA and SAI, bridged the gap and agreed with bits of each of Baldwin’s, Ohiyesa’s, Montezuma’s, and Winnemucca’s strategies. She repurposed her education from the boarding school system (the White’s Indian Manual Labor Institute) and Earlham College to hone her oratory skills and work for federal office, like Baldwin and Ohiyesa, and also attempted to expose U.S. policies, as did Baldwin, Ohiyesa, Montezuma, and Winnemucca (Calloway 2019, 415). She also agreed with Baldwin and pushed back on Montezuma’s critiques of Native people who worked in federal offices, but tensions rose between Baldwin and herself as she focused the SAI’s writing on the experiences of her own Nation and created sharper criticisms of the OIA than her counterpart (Cahill 2013, 81).

In all, many Native people in the Progressive Era “who were educated at government schools […] used their new facility with English and their understanding of American institutions to lobby for changes in Indian Office policies,” “petition the courts to hear their grievances,” and to protest colonial injustices in general (Hoxie 2001, 21). Native figures like Ohiyesa, Baldwin, Bonnin, Montezuma, and Winnemucca did not all agree on what their activism should look like, however—indeed, tensions sometimes arose over these disagreements. Nevertheless, each activist is tied together by the common thread of finding unique and powerful ways to repurpose colonial education systems to advocate for and affirm the humanity of Native nations and their citizens.

Works Cited

Bain News Service. Mrs. Marie L. Baldwin. 1914. George Grantham Bain Collection. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. Accessed via https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mrs._Marie_L._Baldwin_(LOC)_2.jpg.

Beane, Syd. 2018. Ohiyesa: The Soul of an Indian: The Life of a Prolific Native Author, Lecturer & Physician. Vision Maker Media. https://carleton.kanopy.com/video/ohiyesa-soul-indian.

Calloway, Colin G. 2019. First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History. Sixth edition. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, Macmillan Learning.

Cahill, Cathleen D. 2013. “Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin: Indigenizing the Federal Indian Service.” Studies in American Indian Literatures 25 (2): 65–86. https://doi.org/10.5250/studamerindilite.25.2.0065.

Deer, Sarah. 2019. Safety for Our Sisters: Ending Violence Against Native Women – 2 Sarah Deer. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wz-kswpgMgU.

Hoxie, Frederick E., ed. 2001. Talking Back to Civilization: Indian Voices from the Progressive Era. The Bedford Series in History and Culture. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins.

Montezuma, Carlos. 1914. “What Indians Must Do.” The Quarterly Journal of the Society of American Indians 2 (4): 294–99.

Portrait of Dr. Charles A. Eastman. 2020. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dr_Charles_A_Eastman.jpg. Originally published in The American Indian Magazine 6, no. 4 (1919). http://archive.org/details/DKC0238.

Portrait of Zitkala-Sa (Gertrude Bonnin), Dakota Sioux Indiana, 2020. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zitkala-Sa_American_Indian_Stories.jpg. Originally published in American Indian Stories, Zitkala-S̈a (Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press, 1921). http://archive.org/details/americanindianst01zitk.