Fall 2021

“It requires no seer to fortell or forsee the civilization of the Indian race as a result naturally deducible from a knowledge and practice upon their part of the art of agriculture.”

Department of the Interior, Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs – 1885, John D.C. Atkins. 1885.

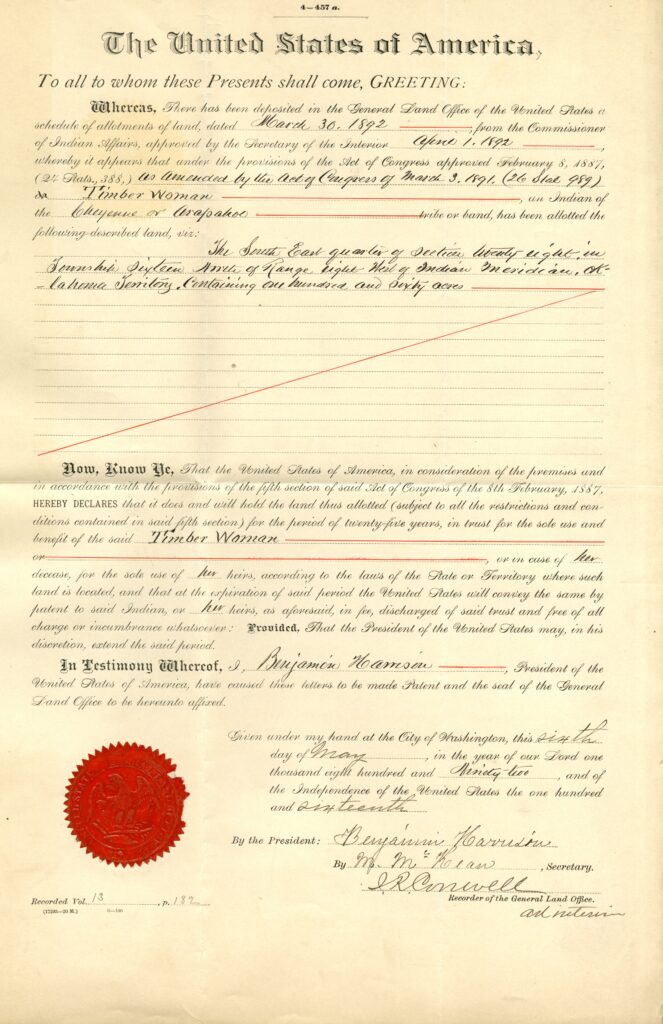

On February 8th of 1887, the United States Congress passed the Dawes or General Allotment act. This policy was one in a long string of detribalization and civilization policies put in place by the federal government to eradicate Indigenous lands and culture.1 Under this act, reservation lands were divided, surveyed, and assigned under the following stipulations:

- Reservation lands would be surveyed and assigned to the male head of a family with additional sections added for people over the age of eighteen

- The lands were to be selected by the allotee, and if they did not the surveyor would choose for them

- The government will hold these lands in trust for twenty-five years so cultivation practices of the land can be learned, then they may have the deed to the land

- After this time and the deed to the land is obtained, the resident on the land is subject to the laws of the state that they reside in

- Unassigned land will be sold as surplus to non-Indigenous homesteaders

- Once the allotee has proved to have “adopted the habits of civilized life,” they can become a citizen of the United States3

But what are these “habits of civilized life”? The Annual Reports from the Commissioner of Indian from the years surrounding the passage of the Dawes Act, reflect a definition of civilization that is synonymous with individualist land cultivation through farming and participation in the capitalist economy of the United States. This reflects the idea that the main value these Indigenous communities had to the federal government was as individual agrarian laborers.

Department of the Interior, Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs – 1885, (V).

“They must abandon tribal relations; they must give up their superstitions; they must forsake their savage habits and learn the arts of civilization; they must learn to labor, and must learn to rear their families as white people do … In a word, they must learn to work for a living.”

Through the division of their tribal lands, the federal government hoped to instill individual drive and remove the confines of collective land ownership. Through this, they believed, that civilization of Indigenous nations was possible. And that in order to achieve the solution to their “Indian problem” allotment must work in conjunction with the education of Indigenous children through the boarding school system. Through these combined processes of land division and the teaching of manual labor skills in boarding schools these texts construct Anglo-American farming as the means of assimilation and eventually obtaining citizenship for Indigenous people.

While these policies are systematically designed to limit indigenous lands while also producing financial gain for the federal government, they also construct an image of what the government wanted from its Indigenous populations and what they wanted Indigenous people to be. That through separating the lands, instilling individualistic land ownership, and learning to cultivate the earth through Anglo-American farming practices, the government intended to assimilate them into the larger society of the United States through their economic participation therefore “adopting the habits of civilized life.”

Works cited

1 Colin G. Calloway, “Kill the Indian and Save the Man,” in First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History, 370-405. Boston, Massachusetts: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2019.

2 General Allotment Act, section 6.