Fall 2021

In discussions of rethinking the practice of history, looking at the story of Ohiyesa, or Charles Eastman, is not a bad place to start. Born a Dakota man and subsequently assimilated into white society as a physician and writer, Ohiyesa presents a variety of nuances to untangle. These nuances speak well to the idea of the desire-based model of historical research. This model seeks to encapsulate the contradictory and complex nature of the human beings behind history, rather than simply focusing on the damage done in the past, which risks painting indigenous communities in the present as broken. Here, we’ll recount Ohiyesa’s life and elucidate its complexities, which reveal the need for a desire-based model of history.

Ohiyesa was born on a reservation in Minnesota and was named Hakadah (‘Pitiful Last’) due to his mother’s death during childbirth. At four years old, whites invaded his home, and his father was captured and presumed executed. His family fled to Canada. He earned the name Ohiyesa (‘The Winner’) for winning a game of lacrosse. However, one day his father returned; he had not died but instead had been ‘assimilated’ by whites. His father was set on having Ohiyesa and his siblings attend the boarding schools that were being opened during the time. These schools were an attempt to “kill the Indian, save the man,” and thousands of Indigenous children were forced to go to these schools and be stripped of their culture. Ohiyesa expressed apprehension in his book From the Deep Woods to Civilization, stating:

“I didn’t want to go back to that place again, but Father’s logic was too strong for me.

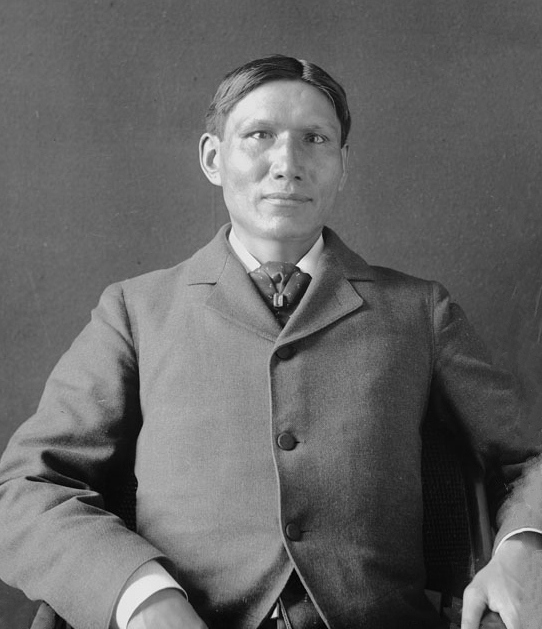

Charles Eastman

And the next morning, I had my long hair cut off, and started school in earnest.”

His educational journey continued into college, attending Dartmouth College and then Boston Medical school, becoming the second Indigenous doctor in America. He started off working in Pine Ridge where he both met his wife and was a witness to the Wounded Knee massacre. He moved to St. Paul and began writing. He authored several books that were read and acclaimed by millions of readers. These books tell of his life, tailored to a white audience unaware of the individual experiences of Indigenous people.

Ohiyesa was also involved in a variety of projects that sought to better the lives of Indigenous people. He was one of the founders of The Society of American Indians. He worked with the YMCA, helping to establish centers by reservations, reaching out to young Indigenous people. On the other side of the coin, he worked with The Boy Scouts of America, seeking to educate young whites on the values and importance of Native cultures. He lectured to many and rubbed shoulders with a variety of influential American celebrities, including presidents.

Where things get foggier are Ohiyesa’s attitudes towards assimilation. Ohiyesa was an advocate for assimilation, not necessarily viewing it as something good, but rather as a necessary adaptation for Indigenous Americans in a changing world. He wrote in Indian Boyhood that:

“The North American Indian was the highest type of pagan and uncivilized man… But the Indian no longer exists as a natural and free man. Those remnants which now dwell upon the reservations present only a sort of tableau — a fictitious copy of the past” (Eastman).

Critics have also noted his use of Indigenous garb when lecturing, which Ohiyesa sought to use as a way of reversing stereotypes rather than promoting them. All of this is to say that Ohiyesa is a complicated figure. Just as he used his writings to reveal the violence and injustice that settlers performed against Indigenous peoples, he was an advocate of assimilation. As a result, he is a heavily debated figure in regards to his overall impact in activism and even his own identity as an Indigenous person.

Such nuance begs for the application of the desire-based model of history. Boiling Ohiyesa down to being one thing or the other would do a disservice to his role as a human being; even worse, by hyper fixating on the white aspects of his identity, it could risk dampening the perception of his works’ impact. Ohiyesa, like other human beings, is a product of a variety of unique experiences. His work in activism comes from a background of experiences both Indigenous and white, a set of two contradictory, oscillating worlds and identities. In order to learn from Ohiyesa, and hence understand more about Indigenous activism and the period in which he lived, we need to use the desire-based model to view his humanity in full, or else risk losing the important nuance that would enrich the historical narratives we craft.

References

Beane, Syd, dir. 2018. Ohiyesa: The Soul of an Indian. Vision Maker Media.

Calloway, Colin G. 2019. First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History. 6th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Eastman, Charles A. 1920. From the Deep Woods to Civilization: Chapters in the Autobiography of an Indian. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company.

Eastman, Charles A. (1902) 2001. Indian Boyhood. Scituate, MA: Digital Scanning, Inc.

Tuck, Eve. 2009. “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities.” Harvard Educational Review 79 (3): 409–27.